Please wait until the ride has come to a full and complete stop is now available in print and Kindle editions.

Through laughter and tears, I invite you to come share my final journey with my brother.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

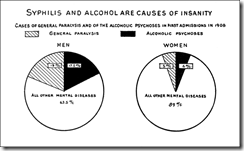

Think mental illness is something new?

It’s not; it’s always been with us.

We may believe our understanding has come a long way, but throughout Jewish history, we’ve wrestled with questions of what causes mental illnesses, and how to treat people among us who suffer from them.

In Jewish law, a person who is insane is referred to as a shoteh, and there are very specific guidelines as to how we should treat them. But let’s look at the definition first.

What is a shoteh?

The Talmud conveniently provides not a translation, but a definition, in masechet Chagigah. The shoteh is:

- · he who goes out alone at night,

- · he who spends the night in a cemetery, and

- · he who tears his clothes.

- · Later, a second baraita adds a fourth criterion: he who destroys all that is given to him

While this probably wouldn’t satisfy a modern psychiatrist, it’s not a bad start.

More important is the broader picture: setting out a definition helps us not merely define the disease, but attempt to create a compassionate situation where both the shoteh and his community are protected from its ravages.

One other beautiful idea encapsulated in the halachic approach: this status is not irreversible.

Nobody is declared a shoteh for life. Instead, there is hope, right until the final hour.

Reb Moshe Feinstein ruled that a person who had been considered a shoteh and ate matzah while in his delusional state must repeat the act a second time once he enters a period of remission (presumably, if it’s still Pesach).

Any of us, at any time

A shoteh is not who you are. It’s something you’re living with at any given moment.

There are parallels in the modern mental health system (though they don’t always work as well as they should), which take away a person’s decision-making power – and the extent to which he’s held responsible – during times when he’s relapsing into illness, and returning it to him when he’s in a period of remission.

I say “him,” when I should really say “us.”

In halachic terms, as in medical terms, mental illness is not something that only happens to others. It can happen to any one of us, at any time, and that’s why the halacha treads so carefully, and with so much compassion.

In terms of protecting the people around the shoteh, the Talmud (Ketubot 48a) says that a beit din (rabbinical court) is allowed to take away his property and use it to support his wife and children on the grounds that, if he was sane, he would surely want to take care of this responsibility himself.

And when we talk about protecting the shoteh, we have the gemara in Yevamot (112b), which says that a husband may not divorce his wife while she’s insane.

A person with a mental illness is considered a choleh she-yesh bo sakanah, one who is sick and whose life is in danger, to the extent that Shabbat observance can be suspended to help them get treatment or take medications.

And in that, the halacha shows a deep understanding that even many of us “enlightened” and “accepting” members of society don’t fully grasp:

Mental illness is a deadly disease.

With this disease, death doesn’t come through the body’s withering or fading, but the withering and fading of the mind. As the mind loses its grasp on reality, it slips away. Over 40% of people with schizophrenia try to kill themselves; 10-15% eventually succeed.

Many of the rest die from accidents related to their disease: fires they have set themselves, substances they have eaten or drunk, fights they have picked with others, or simply freezing to death from misjudging the weather conditions.

Schizophrenia and other mental illnesses can kill, just as surely and brutally as any other disease.

Madness in the Tanach

David HaMelech had a deep, deep understanding of Hashem’s creation. Yet even he admitted in a midrash (1 Shmuel 26) that there were three things whose point he’d never understood:

- · The web-spinning spider

- · The stinging wasp, and

- · The madman

This midrash goes on:

“When a man walks in the market and he drools over his clothes and children run after him and the people make fun of him; this is beautiful before You?” The Holy One blessed be He said to David: “You complain about the injustice of insanity; by your life you will regret this and you will pray for it until I give it to you.”

Later, David HaMelech was convinced of the “benefits” of madness when he had to escape from King Achish of Gat. He begged Hashem to make him insane, acting so abhorrently that Achish saw no choice but to send him away.

We have to understand this a little more closely. Although it says in Tehillim (34) that David “disguised his sanity,” only true madness would have made the great king drool and act like a crazy person in a way that seemed fully authentic.

And then, just as with the shoteh, it was gone.

Not only was David HaMelech back in control of his senses, his vision was clearer and sharper than ever; some of his greatest words of wisdom are encapsulated in Tehillim 34, written at the blessed return of his own sanity.

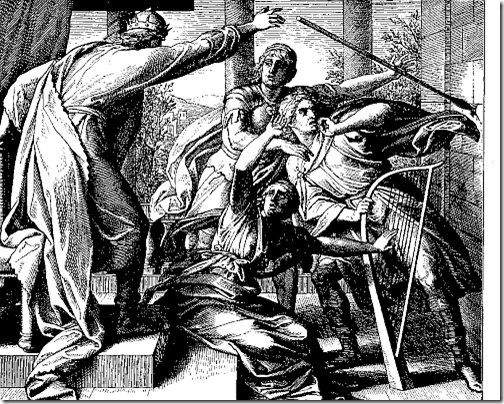

This wasn’t the first time David HaMelech had encountered madness.

We read about this in Shmuel Alef. Remember how, as a boy, he came with his harp to play for Shaul? That’s because the great king had temporarily gone crazy. Hashem’s spirit was suddenly gone, and an “evil spirit” has replaced it.

וְרוּחַ ה סָרָה, מֵעִם שָׁאוּל; וּבִעֲתַתּוּ רוּחַ-רָעָה, מֵאֵת ה.

Now the spirit of Hashem had departed from Shaul,

and an evil spirit from Hashem terrified him.

Very odd: Hashem’s spirit is “gone,” and then a different spirit comes upon Shaul, also from Hashem.

Madness isn’t something external or foreign, as we’ll see. It’s just as much from Hashem as the “sane spirit” that overtakes Shaul in his better moments.

How can something so ugly be from Hashem? That is the eternal question, and one I can’t really answer here.

Madness in traditional Jewish understanding

Madness in traditional Jewish understanding

The classic story of insanity in Jewish tradition comes to us in Chagiga (14b):

Four men descended to the “Pardes” (orchard of Torah learning): Ben Azzai, Ben Zoma, Acher [Elisha ben Avuya] and Rabbi Akiva.

Ben Azzai went in, saw what was there, and died.

Ben Zoma went in, saw what was there, and went mad.

Acher went in, saw what was there, and left the life of Torah.

Rabbi Akiva, it’s said, entered in peace and left in peace.

Every one of these is a complete story in itself, but Ben Zoma is our question right now. What did he see? And how did it make him go mad? Great questions… and again, questions I really can’t answer here. I don’t know if anyone knows.

First of all, Ben Zoma, like King Shaul, was no ordinary mind. This was the man who, in Pirkei Avot, taught us the secret of wisdom: “Who is wise? The one who learns from all men.”

How could someone so great fall so low, so fast?

That is the essence of the shoteh; it can happen to any one of us, at any time. The spirit of madness, as with Shaul, also comes from Hashem.

However, every source I looked at tried to blame Ben Zoma, or at least find in him spiritual failings that would cause his mind to shatter so easily. Blaming the victim, then as now, is something all-too-common in every type of mental illness.

Two dangerous ideas

We’ve all probably come across two harsh and counterproductive ideas that are examples of how we, as Jews, are not supposed to think. Yet they have been, perhaps, the two most pervasive misconceptions throughout our history:

- · One, that mental illness is a phenomenon like a dybbuk, where a person is “possessed,” and

- · Two, that mental illness is in some way a punishment.

I asked Rabbi Mordechai Torczyner, Rosh Kollel of Toronto’s tiny YU branch, because he has a strong background in medical issues and slightly off-the-beaten-path halacha, for some guidance on these two points.

His answers were very helpful to me. These days, we may roll our eyes at the dybbuk thing, but at various times in our history, one of the most common ways to “cure” mental illness was through exorcism.

Here’s what Rabbi Torczyner told me:

The idea that this is a dybbuk stems from an old idea that a soul might return to Earth and enter someone's body. It's an ancient idea, not necessarily originating in Judaism at all, but some are ardent believers in it, and they will use it to explain phenomena that they observe. In the 10th century, Rav Saadia Gaon wrote that some people see an animal that exhibits behaviours similar to their deceased relatives, and they conclude that this is a new incarnation of the relative; he was not impressed.

Neither am I.

But if it sounds like the idea of a dybbuk is something out of the 18th century, think about some of the ways we talk today.

Have you ever said “I’m not myself today”?

What about, “I don’t know what got into me?”

Dybbuks may not be in the forefront of our minds, but this idea, that an ordinary person is in the grip of something extraordinary or supernatural is an astonishingly pervasive one, even in our modern “scientific” culture.

The idea that this is a punishment is horrific and repulsive, but I can see how people get there. They start out with the concept that reward and punishment exist in this world - an idea that may be wrong (indeed, some passages of gemara contradict it), but is not beyond the pale of Judaism (other passages of gemara support it). They then confront a case of someone suffering, and they cannot believe that Gd would permit this, unless the person deserved it. So they conclude that it is punishment for something. This is seen in the narratives of Iyov's friends, who try in various ways to get him to accept that his suffering must be punishment for his sins. Ultimately, Gd comes and blows them out of the water, but it takes a few dozen chapters to get there.

Rabbi Torczyner’s responses reflect the compassionate ideas rooted in the halachic understanding of the shoteh.

Dividing the waters

Rather than blaming Ben Zoma, then, let’s look at his own words, right after the Pardes experience, when asked by another rabbi where he’d been:

“I was contemplating the mysteries of creation. I learned that between the upper waters and the lower waters there are but three finger-breadths.”

Hearing this, the rabbi told his students, “Ben Zoma is gone.”

The “upper and lower waters” are described in the story of Creation, back in Bereishit. On the second day, Hashem divides between the two types of waters, mayim and sha-mayim.

Rabbi Yissocher Frand says neither water was more or less “valid.” This wasn’t a case of good and evil, or true and false. In separating these waters, Hashem has drawn an arbitrary distinction between two equal things.

And here we see the very essence of sanity.

Sometimes (my thoughts, not Rav Frand’s), we need these arbitrary distinctions in the world; toeing this line is what marks us as “sane” in ordinary society.

When the distinctions begin to blur, as they did for Ben Zoma, when the upper waters start to seem like they’re the same as the lower waters – or at least, only three finger-breadths apart – then our sanity is in trouble.

One line often left out of the Pardes story is Rabbi Akiva’s exhortation to the other three before they ascend to see whatever it is that they end up seeing. He says, “When you get there, don’t say ‘water, water!’… for it is said, 'He who speaks untruths shall not stand before My eyes' (Psalms 101:7).”

Although there is really no distinction between water and water, keeping the ideas separate is crucial enough for Rabbi Akiva to call this blurring a fundamental “untruth.”

My brother Eli lived the last part of his life, twenty years or more, in a world of untruth Rabbi Akiva could easily have recognized.

Schizophrenia is a world of lies.

With this disease, your senses fail, not in the ordinary way, of deafness and blindness. You can see and hear, alright. But what you see may or may not be real. What you hear may or may not be the truth. Friends and family can start to look like enemies, or at least, conspirators.

Water that is above can start to look a lot like water that is below.

Sanity and Jewish responsibility

No wonder the rabbi told his students “Ben Zoma is gone.” Without rationality, the ability to see these distinctions, he couldn’t really function anymore, either as a rabbi or as a Jew.

That’s because although Hashem created the world originally, it is our job to partner with him in its ongoing operation. It’s an important job, and it’s one that falls only to those whose sanity, whose perception of these arbitrary distinctions, remains intact.

As Jews, we exercise our power of discernment every week after Shabbat, when we praise Hashem for distinguishing between light and darkness, holy and profane, Jews and non-Jews.

But perhaps the best example of this responsibility comes with Rosh Chodesh. In the time when the Sanhedrin sat in Yerushalayim, the new month couldn’t begin until the moon was sighted by two witnesses. These witnesses had to travel to the Sanhedrin to tell the rabbis all about it.

They didn’t get off easily, either.

The rabbis would interrogate them: “At what angle did you see the moon? In what position? What did it look like?”

Here’s the thing: The rabbis of the Sanhedrin knew the answers already.

Even in those days, trained astronomers could predict when and where and how the moon would be sighted each month. Nevertheless, until it was seen by a reliable witness, it basically hadn’t happened yet. The arbitrary distinction between truth and falsehood lay solely in the accuracy of the witnesses’ perception.

Their sanity, in other words.

This isn’t just any old mitzvah. Rosh Chodesh is the very first mitzvah Hashem gave to the Jewish people, to keep time and mark the months, and here it is, so very contingent on our rationality.

Happily for Ben Zoma, perhaps, he died soon after the Pardes story took place.

In real life, people live for years with insanity. And those of us around them, those of us in society, have to wrap our own minds around how and why something like this could happen.

Unless we look the other way, ignore them, describe what they’re going through as “emotional disturbances.” Saying, “he’s a little… off.” Not calling it what it really is.

A miserable life, with a deadly disease.

Schizophrenia doesn’t always kill its victims, but then, neither does cancer. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t take it seriously. It kills often enough that we all ought to pay attention.

Suicide and Jewish burial

You may have heard that a person who kills himself can’t be buried in a Jewish cemetery.

Perhaps that’s true if they do it with full intention, in their right mind. But as the halachas of the shoteh show, even before the modern era, Judaism had a full and rich understanding of what it means to be in one’s right mind – and why we must exempt those who aren’t.

When I heard that we’d be holding my brothers’ burial at his graveside, rather than in comfortable seats at the funeral chapel, I had one main concern: that people would think he was less worth honouring; that we were burying him surreptitiously because of the way he died.

Because of his disease.

I was comforted by the many friends and family members who turned out on that sunny Tuesday afternoon, but more than that, I was comforted by the words of one of the rabbis from our shul who explained that when a person suffers as much as Eli did, they are not responsible for any of their actions – right up until the end.

Not only not responsible: Such a person is to be held on the level of a tzaddik, as one who fought an honourable battle, bravely and to the extent of his abilities, and who will be welcomed with open arms in shamayim, immediately.

I cannot imagine what Eli was battling all those years. Yet, as this rabbi pointed out, he never once tried to hurt any of us, or anyone else; he always spoke kindly to the children and brought them weird little gifts.

That was his true character shining through a very hazy windowpane; his inner strength and character that shows us it was not that a dybbuk had taken hold of him, but just his own mind, terribly, terribly twisted.

The gift of Eli

My mother also reminded us that, thirty years ago, he refused to attend his own bar mitzvah if my parents held a big celebration in the shul; you know, the kind of shindig mine had been two years before. So they made a small party at home and Eli was happy.

His funeral, then, was the equivalent of a small party at home. I like to think he was happy that nobody had to get dressed up or sit through a long, boring service.

Beyond a better understanding of his disease, the greatest gift of the past month has been getting Eli back.

Am I allowed to call it a gift?

Unshadowed by the gloomy, shouting, anti-social presence he’d become, the brother I knew has surfaced again through photographs, through stories. We have finally been allowed to enjoy him once again.

It’s the opposite of what we saw with King Shaul. The “evil spirit” has departed from Eli… and he is back where he belongs, in the glow of the shechina, in the world of truth once more.

Yet even as we’re grateful for the gift of having him in our midst again for this short time, we also have to let him go: brother, uncle, son, childhood companion and friend.

The stages of mourning in Jewish life teach us the pattern of gradually letting go.

At the end of the shiva period, we got up and walked with Eli out of the house. Not with anger, not amid shouting, as happened a few times in his life. With peace and love and memories.

Now, at the end of this shloshim period, we give him one last hug and send him even farther than we can possibly go yet ourselves. We promise him the journey will be wonderful, the wisdom infinite, the light and truth a fountain for his weary soul.

As David HaMelech wrote after he was delivered, alive, from his own battle with insanity:

צָעֲקוּ, וַה שָׁמֵעַ; וּמִכָּל-צָרוֹתָם, הִצִּילָם.

They cried, and Hashem heard,

and delivered them out of all their troubles.

There is nothing new here. History repeats itself, and will keep on repeating itself. Water, water, everywhere, and the distinctions sometimes so hard to see.

And yet every individual, every story, is unique, and my brother’s soul is stronger than ever now, unburdened from its disease. May Eli’s neshama help those who still suffer; may his bright spirit and gifted mind intervene to ease the pain of others.

May the shining light of the World of Truth continue to comfort him, and the knowledge that he is surely there already continue to comfort us as well.

# # #

[public-domain images: Saul Tries to Kill David, by von Carolsfeld; David and Saul, by Marc Chagall, Rabbi Akiva, from the Mantua Haggadah]

This is an amazing piece of writing and a beautiful testament to your brother. May his memory be for a blessing.

ReplyDeleteThis is a very thoughtful write-up on a painful topic. I especially appreciate the interesting d'rash on the Pardes encounter--certainly one of the most enigmatic accounts in the entire Talmud.

ReplyDeleteHaving battled PTSD for years, I can confirm that sanity is not always well-defined. Sometimes, the past seems more real than the present and it can take a great effort to bring one's inner world back into alignment with the outer world. To be in a state where that alignment can't be accomplished by any act of will, where there is no way to differentiate world from world...that is a terrifying thought.

Yishar Kokhech for handling this topic with such eloquence and sensitivity. May your brother's memory be a blessing for you.

@yael, I appreciate your honesty. Maybe it's just our family, but in our family, we have always sort of recognized sanity as a spectrum, on which we all slide at different points in our lives.

ReplyDeleteI resisted including the Pardes narrative because it is trotted out so very often, sometimes to make whatever point it is the person wants to make about staying on the derech, but in the end, it was calling to me. :-)

Jennifer, I'm sorry to hear of your loss (I just found out recently), and thank you for writing about what the loss and the gift of Eli means to you. I am a couple of years younger but knew him in high school and we also coincidentally went to the same university.

ReplyDeleteMD, thank you so much for stopping by and letting me know. I really appreciate it.

ReplyDeleteVery moving , but not in a good place in more ways than one to benefit. Kosher and Happy Pesach,

Delete