How many dreams does Yosef have in this week’s parsha?

I’ve always thought it was two. Maybe you did, too?

But if you look very carefully into the actual text, you’ll notice something funny. (Or, if you’re like me, you won’t – at least, not at first.)

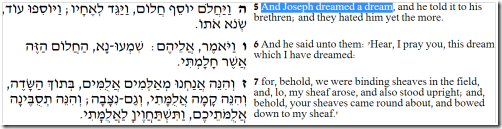

Here’s how Yosef’s dreaming begins:

What’s the sequence here?

1. Yosef has a dream, tells his brothers, and they hate him more.

2. Yosef begs his brothers to hear his dream.

Huh? Didn’t they just hear him tell a dream? Of course they did, because the Torah says right there that hearing his dream made them hate him more.

After this, the Torah goes on:

3. Yosef tells his brothers a dream where they are gathering sheaves (wheat). This is often called his first dream.

(Is it really???)

4. Yosef tells his brothers a dream where the stars, moon and sun are bowing down to him. This is often called his second dream.

I’m sure you see the obvious question. What did Yosef tell his brothers in #1?

According to most interpretations, the Torah is being a little redundant here. The dream in #1 is the “first dream,” the one about the wheat sheaves. The story is just being drawn out for whatever reason.

But there is a minority opinion – of course.

According to the minority opinion, which is that of the Chizkuni but not many others, the first dream was a totally different dream.

The Chizkuni writes, “this dream is not mentioned because it did not come to pass.” (חלום זה לא נתקיים לפיכך לא נכתב)

Which dreams are fulfilled?

So according to the Chizkuni, this first dream didn’t come true. Therefore, it wasn’t worth mentioning (a weird retroactive kind of reasoning, but that’s the way it is with Hashem sometimes).

But this explanation leaves us with another question: Why didn’t it come true?

There is a tradition in Judaism that “The fulfillment of a dream depends on the way it is interpreted.” This actually comes straight from next week’s parsha, where it says,

וַיְהִי כַּאֲשֶׁר פָּתַר-לָנוּ

“It came to pass, just the way he interpreted it for us.”

This idea is also found in the Talmud, which says “all dreams follow the mouth.”

R. Bizna b. Zabda said in the name of R. Akiba who had it from R. Panda who had it from R. Nahum, who had it from R. Biryam reporting a certain elder — and who was this? R. Bana’ah: There were twenty-four interpreters of dreams in Jerusalem. Once I dreamt a dream and I went round to all of them and they all gave different interpretations, and all were fulfilled, thus confirming that which is said: All dreams follow the mouth.29 (Brachos 55b, Source)

Here’s one awesome story that demonstrates this, from a book called Narratives of the Talmud (1995, source).

A woman came before Rabbi Eliezer and said to him, “I had a dream in which the pillar of my house broke.” He said to her, “That means you will give birth to a son. [The pillar on which the house is supported is a symbol of her womb, which houses the embryo and which bursts open at birth.]” She went away and gave birth to a son.

Some time later, she was looking for him again. His students said to her, “He is not here. What do you need him for?” She answered, “I had a dream in which the pillar of my house broke.” They said to her, “It means, that woman’s [i.e., your] husband will die. [The husband supports the house like a pillar].”

When Rabbi Eliezer came, they told him the whole story. He said to them, “You have murdered! Why? After all, the fulillment of a dream depends entirely on its interpretation, as it says (Genesis 41:13): “It came to pass just as he had interpreted to us.’”

So it is possible, I suppose, that the first dream didn’t come to pass because it wasn’t interpreted; Yosef told the brothers what was in the dream, but they didn’t care enough to interpret it seriously. Therefore, because it was never interpreted, it never happened.

But wasn’t Yosef this great big “big shot” when it came to interpreting dreams?

Maybe so. But it seems like when it comes to his own dreams, he needs his brothers’ help. I found some support for that in an explanation I found for the first dream in a book I’d never heard of called “Diyukim LaTorah” (1956, Source).

(I’ve translated the full text in the appendix below, because I couldn’t find it in English, and it’s fascinating.)

What was in that first dream?

There, it says the brothers hated him when they heard the first dream, but they didn’t think it had anything to do with them. They just thought he was being a show-off.

That first dream, Diyukim LaTorah says, was therefore probably about something mundane. You know, the run-of-the-mill kind of dream that is easily forgotten. They were shepherds; so it probably had sheep in it. And there was a number, like in the other dreams, but it didn’t jump out at the brothers because there were ten, not eleven.

That commentary doesn’t say ten of what, or describe exactly the content of the dream either; it just says it was about ten of something, and about shepherding. (Maybe he dreamed that ten sheep were bowing down to him?)

However, contradicting the Chizkuni, Diyukim LaTorah says that first dream actually did come to pass, when the brothers went down to Mitzrayim without Binyamin (so there were ten of them, together).

What made the second dream so important?

Whatever the case with the first dream, in the very next line, Yosef has his second dream. Except now, his brothers are so angry at him that he has to beg them to listen.

Why does he beg them? Because now… he’s terrified.

Diyukim LaTorah says the second dream “shook” him in a way that the first did not. This is probably why it merits more attention in the Torah. Shaken, Yosef can’t figure out his own dream without his brothers’ help.

This does help answer a niggling question I and many others have had: Why does Yosef keep telling over his dreams?

Over and over, Yosef keeps relating his dreams, even though it makes his brothers hate him more. Potentially, relating his dreams instead of shutting up about them already even endangered his own life.

Many responses I’ve seen make him seem hopelessly naïve or childish. But some say that his dreams were nevuah (prophecy) and therefore he had to share. (However, that is usually only true if Hashem expressly tells the navi he must go and relate his message.)

So the idea that Diyukim LaTorah raises, that Yosef needed his brothers’ explanation of his dreams, is a compelling one.

If it’s true, as the sources we’ve seen here suggest, that a dream must be interpreted in order to come true, then it’s also possible that a dream must be interpreted by someone other than the dreamer in order for it to come true.

Therefore, even if Yosef’s dreams are all about pride and haughtiness, he needs his brothers to interpret them, to speak them aloud, so they’ll come true. And he desperately wants them to come true, because on some level, he wants to rule over his brothers.

Maybe Yosef was just stuck up?

But does wanting his “haughty” dreams to come true mean Yosef is just “stuck up” or proud?

Absolutely not. Because he knows his only family history very, very well.

And look at what he’s seen in the past few generations of his family. In each generation, only one person has been chosen to receive the “legacy” – the two precious gifts Hashem promised Avraham. These are eretz and zera, a holy land and holy descendents.

Avraham passed these gifts along to Yitzchak, cutting off Yishmael (yes, he received a different birthright, but one far less valued in our tradition).

Yitzchak passed them on to Yaakov, cutting off Eisav (true, he did this to himself by selling his birthright).

And soon, Yosef probably believes, Yaakov will have to choose one offspring to receive the holy gifts, and cut off all eleven others.

So Yosef wants to be picked, with good reason.

He is Rachel’s son, beloved, beautiful, gracious and very exacting in his observance of mitzvos, as we see in all the years he spent in Paroh’s palace, surrounded by avoda zara, yet remaining a dedicated Jew.

So despite his youthful pride, Yosef’s intentions are good. He genuinely wants to crown himself with the crown of Torah.

And for this, he needs his brothers. They are holy people, too, and he hopes that their interpretation will help his dreams come true.

On the surface, his brothers’ words seem to align Yosef’s own ambitions when they say, albeit sarcastically, “Will you indeed reign over us? or will you indeed have dominion over us?”

But is this the best interpretation of the dream of the sheaves?

Here, the brothers see what they want to see. And what do they see?

A youth, dressed up in a fancy coat, their father’s favourite son. They probably also suspect he’s going to be picked to receive the Legacy, cutting all of them off.

What they don’t see is bigger and more important still. They don’t see the seeds of the nation that is about to be born from them all. They don’t see the hand of Hashem, steering Yosef into the role that will play in the destiny, and the redemption, of that nation.

Despite his ambitions, what Yosef will ultimately accomplish is not anything like rulership, or dominion. But it takes him years to figure that out.

Where do dreams come from?

All of this left me wondering about dreams, and how we view them in Judaism.

Do they represent truth? Do they have to come true? Obviously, they don’t, or we would all find ourselves in some very strange situations.

Nevertheless, according to some opinions, a dream is a type of prophecy. The difference is only a matter of degree. (One view says that a dream is 1/60th of a prophecy; it’s nice to put exact numbers on things!)

But there is also the idea in Judaism that dreams can be either true or false. This might depend on their source. I found a Gemara (Brachos 55b) that says,

When Samuel had a bad dream, he used to say, The dreams speak falsely.27 When he had a good dream, he used to say, Do the dreams speak falsely, seeing that it is written, I [God] do speak with him in a dream?28 Raba pointed out a contradiction. It is written, ‘I do speak with him in a dream’, and it is written, ‘the dreams speak falsely’. — There is no contradiction; in the one case it is through an angel, in the other through a demon.

There is also a modern sense in which dreams are either “true” or “untrue,” which follows from the psychoanalytic theory of Sigmund Freud. In Freudian analysis, writes one psychologist, the interpretation of dreams “became a core component of classical psychoanalytical treatment, as a means to address the unconscious source of the client’s presenting problem.” (Source)

So dreams are in some sense both true and useful, “offering a window to our hearts and minds, and oftentimes, their message is one that we know all along but for whatever reason cannot bring to the surface.”

However…

Today, we’re not on the same level as Yosef. We all know this intuitively.

Even in the Gemara, it says that most dreams “are not indicative of any sign or message being communicated by Hashem… The Tosefta in Ma’aser Sheini (5:6) states clearly and succinctly that dreams have no effect at all, either positive or negative.” (source)

As with Yosef’s uninterpreted first “mundane” dream about sheep, our own dreams are more influenced by the stuff that happens to us every day, and what we ate before bedtime. So we shouldn’t expect deep revelations.

Is this inconsistent with the Gemara and the stories we saw earlier saying the significance of a dream is in it interpretation? Most opinions say it’s completely consistent. It just means that the dream, in itself, has no significance.

In order to figure the whole thing out once and for all, the Abarbanel (1437–1508) on Parshas Mikeitz says that there are two different types of dreams:

· Dreams with physical influences – irrelevant in terms of halacha / nevuah

· Dreams with a message from Hashem – possibly significant and valid

The best way to figure out which is which, the Abarbanel said, is “to examine the orderliness and straightforwardness of the dream, as well as the impact it has on the person having the dream.”

What impact do dreams have on us?

As we see in Diyukim LaTorah, when Yosef dreamed about the sheaves, he awoke feeling “shaken.” Therefore, he believed this second dream was one with a message from Hashem – one he needed to pay attention to, and one he wished to be fulfilled. (See my translation below for the exact details of his response to both dreams.)

By the way, Judaism also contains many teachings about what to do when we have a bad dream, one we don’t want to be fulfilled… a dream which has “shaken” us as Yosef’s dream has.

Maybe you’ve seen in the siddur, during Birkas Kohanim (duchening, the Priestly Blessing), a little tefillah that people can say in between the verses.

I had skimmed it many times, but sister Sara brought to my attention a few months ago just how fascinating and bizarre it is. Here’s how it goes:

“Master of the World, I am yours and my dreams are yours. I dreamed a dream that I do not understand its meaning — whether it is something I have dreamt about myself or it is something that my friends dreamt about me or whether it is something that I dreamt about them. If these dreams are indeed good, strengthen them like the dreams of Yosef. However, if the dreams need to be healed, heal them as Moshe healed the bitters waters of Marah, as Miriam was healed of her tzaraas, as Chizkiyahu was healed of his illness and as the waters of Yericho were healed by Elisha. Just as You changed the curse of Bilaam to a blessing, so, too, change all my dreams for the good.”

In the context of our parsha, notice that this text emphasizes that the dreams of Yosef were good dreams, even though he was “shaken.”

Can we “heal” our dreams?

This idea of “healing” dreams comes up repeatedly throughout Jewish sources. There’s even a traditional prescription for fixing a troubling dream: the Taanis Chalom, a day of fasting, to cure the troubling dream.

Rabbi Berel Wein says this “is deemed to be such a powerful weapon against the depression caused by nightmares that one is allowed to fast even on Shabat, a day when no fasting is usually allowed… due to the intense psychological pressure and depression that a bad dream can cause to a person.” (source)

(He also says that someone who fasts on Shabbos should fast another day afterwards as penance!)

Why is a bad dream taken so seriously, that a person can even violate their celebration of Shabbat to take care of it? Because, as I mentioned before, dreams are considered a form of nevuah (prophecy, and here’s another source).

However, in our time, fasting to heal dreams is almost unheard of. I read in the name of the Chazon Ish (Avraham Yeshaya Karelitz, 1878-1953) that, “Today’s people are not people and today’s dreams are not dreams” (source).

In Yosef’s time, in the time of the Tanach and maybe even the Talmud, dreams might have had all kinds of meaning. Then, the statement that they are prophetic and/or useful might have some truth to it, or psychological validity, as Freudians believe.

But today, our minds are too clouded to ascribe much significance to the stuff that goes on in our heads at night.

In the time of Yosef, however, dreams were another thing altogether…

What does this have to do with Yosef?

Clearly, Yosef is very, very gifted at interpreting the dreams of other people. But in the opening of this week’s parsha, it has become pretty obvious that he is not very good at interpreting his own dreams. He is shaken by them, confused, and he has to ask his brothers and his father to interpret them.

Then again, he is still very young.

I’ve always wondered why most meforshim seem dead set on attacking Yosef, ascribing bad motivations to his actions, dwelling on how he sucks up to his father, preening, dressing up, running around telling on his brothers instead of just letting them be.

Remember, though: when meforshim seem to “gang up” on a character in the Torah, it’s not because they have their own agenda. They’re just trying to serve the agenda of the Torah as they perceive it.

So what are they perceiving here in the story of Yosef?

Yosef, it turns out, gets more attention than almost any character in the Torah. And not only his actions, like we see with Moshe. Unlike most characters in the Torah, with Yosef, we really get to see what screenwriters and storytellers call the “narrative arc.”

The narrative arc is the way the character develops, growing and changing over time. And if you look at Yosef’s arc, it really is tremendous. He goes from this whiny kid to the head honcho of the greatest nation in the world.

There is much for us to learn in the transformation of Yosef over the three parshiyos we get to know him.

And seeing his development as an arc, we can also see that at the beginning, with his flawed, youthful character, Yosef himself may be the greatest obstacle standing in the way of his own success.

Sure, he dreams of success. But not the kind of success Hashem has in mind for him.

Because we’ve read the entire Torah already, we know what Hashem wants in a leader. He doesn’t want a preening, gloating, smirking leader. He wants someone a whole lot like Moshe and David – shepherds, with greatness thrust upon them.

In the beginning of his narrative arc, in this week’s parsha, Yosef makes the mistake of trying to embrace greatness, chase it, even, rather than letting Hashem thrust it into his life.

But more importantly, he made the mistake of believing he understood what greatness was. In fact, he really had no clue just yet.

Who is a Torah leader?

Rabban Gamliel, I read, would reprimand the students he was ordaining (giving smicha): “You think I’m giving you rulership? I’m giving you servitude!” (Horayot 10a-b, via this site).

This echoes the idea in Pirkei Avos, “Do not make the Torah into a crown with which to make yourself [seem] great, or a spade with which to dig.”

In Yosef’s case, the Divine talents he received, his interpretation, his charisma, his intelligence, were not there merely to feed his own pride and make him great.

These dreams Yosef dreams in our parsha, it turns out, are not – to borrow Rabban Gamliel’s words – dreams of rulership; they are dreams of servitude.

Finally, finally, Yosef does figure this out.

A friend pointed out that through all his years of imprisonment and hardship, Yosef never complains. It’s totally true. Nevertheless, I’ve always felt like he also isn’t terrifically proactive.

In the first part of his narrative arc, Yosef doesn’t take a strong hand in his own life. He merely reacts to situations, “putting out fires,” rather than starting them himself.

Don’t get me wrong; he does very well for himself. But he never actively takes hold of these gifts until one sudden moment when he is face-to-face with his brothers again.

The moment Yosef figures it all out…

Look at what the Torah says at that moment. Here’s Yosef, reunited with the brothers who tossed him in a pit, who sold him into slavery. And what does it say?

וַיִּזְכֹּר יוֹסֵף--אֵת הַחֲלֹמוֹת, אֲשֶׁר חָלַם לָהֶם

“And Joseph remembered the dreams which he dreamed of them.”

Because Hebrew is awesome, the words “of them,” can also mean “for them.” And indeed, that really is what it means.

This is Yosef’s moment of revelation. You can almost hear him leaning closer to Hashem in these lines, gradually figuring out what he’s doing here in Mitzrayim in the first place.

Yosef understands at last what those dreams were really all about.

Now, he sees his true purpose, and the hand of Hashem in the extraordinary events of his life so far.

All those dreams were not for him – they were for them, the shevatim. They were the key to how Yosef would help make them all into a great nation.

This generation, Yosef realized, would be different. There was not going to be just one Legacy passed on to one son, but rather, all the sons would now come together – like the stones under Yaakov’s head when he dreamed on Har HaMoriah – to become a single great nation.

That is Yosef’s mission, he realizes at last.

Later on, when Yosef finally reveals his identity to his brothers – after they have bowed before him, fulfilling the first dream – he says to them,

וַיִּשְׁלָחֵנִי אֱלֹהִים לִפְנֵיכֶם, לָשׂוּם לָכֶם שְׁאֵרִית בָּאָרֶץ, וּלְהַחֲיוֹת לָכֶם, לִפְלֵיטָה גְּדֹלָה.

“And God sent me before you to give you a remnant on the earth, and to save you alive for a great deliverance.”

He’s finally figured it out.

Do YOU have the courage to serve?

So what’s the message of all this for us, today?

True, our dreams may not be dreams, and we may not even be “people” in the Chazon Ish’s way of looking at things.

But we are the descendents, the inheritors of that holy Legacy. These stories are more than stories, and Yosef’s dreams are more than dreams.

Many people bristle today at the notion of a Chosen People. Egalitarianism is big now, along with the idea that all beliefs are pretty much equally valid.

Just as Yosef came to realize, however, we must also have the maturity to acknowledge that being Chosen is indeed special… but it is not special in the way of rulership; it is special in the way of servitude.

Last week, I had the privilege of interviewing this man.

This is a man who has given the last thirty years to serving Am Yisrael – the entire Jewish people, all over the world.

He comes from an unusual background, an anti-Zionist Eda HaHaredit family in Meah Shearim, the most ultra- of the ultra-Orthodox world (a phrase I don’t ever use myself, but it may indeed be how they view themselves).

And yet, one day in 1989, he saw a terrorist blow up a bus and realized that we are all in this together. Today, though his family has condemned him, he works with humans of all kinds to help humans of all kinds: Jewish, Druze, Christian, Muslim. It has taken courage, determination, and more than a ton of character… all in order not to rule, but to serve Am Yisrael.

This is something like Yosef’s revelation, although today, it has become a cliché to say it out loud. Say it anyway: We’re all in this together.

In this week’s parsha, and over the next, Hashem offers us a “slow reveal” of his own dream for Am Yisrael. We’re going to see their transformation from a small family to a great nation. The Legacy of Avraham is ultimately passed down not to one son but to 600,000 and today, to millions of us all over the world.

Hashem’s plan, in the end, was to offer Am Yisrael not a single ruler but hundreds of thousands of servants.

May we have the humility to lean closer and hear the message, and may we have the courage to truly serve Hashem and Am Yisrael according to His will.

Tzivia / צִיבְיָה

Appendix

The following is my own partial translation of a text called Diyukim LaTorah (1956), which I found very helpful in understanding the content of Yosef’s first two dreams. (These are from pages 569 and 570; click the page numbers to view the original pages in Hebrew):

ה) בפסוק זה סופר החלום הראשון, אשר תוכנו לא נמסר לנו ואף הוא לא נפתר על ידי האחים כדבר נבואה, כי אם חשבוהו כיצר התנשאות בעלמא. הלומד פסוקים אלה יחד עם פרוש המלים יראה ויבין על שום מה פרש אאמר׳ר זצ״ל ב ״נחלת זאב״ ע״פ הרד״ק כאן את הפרשה באופן זה. תתעורר השאלה: מדוע לא סופר תוכן החלום הזה בתורה, וכן מדוע לא פתרוהו האחים אלא כהתנשאות בעלמא ?

In this passuk, it is related of the first dream, whose content is not passed on to us. And furthermore, is not solved by the brothers as a matter of prophecy, because they thought it only as a creation of mere haughtiness… This raises the question: why is the content of this dream not related in the Torah, and similarly, why do the brothers not interpret it, but rather see it as mere haughtiness?

אחי יוסף היו רועים, וכל העוסק ביום במלאכה זאת, אין זה פלא אם גם יחלום עליה בלילה. החלום עסק כנראה בנושא קרוב לביתם. (עיין גם פרק מ ״ ב ט ׳ ב פרושנו) יתכן שגם התנשאותו לא התבטאה בחלום הזה לפי מספר אנשים בשעור שהאחים יכלו לחשוב שהכוונה הישירה אליהם.

Yosef’s brothers are shepherds and they’re occupied with shepherding all day, so it’s no surprise if someone dreams about that at night. So this first dream was probably on a topic close to them. They saw the dream as haughtiness because of the number of people who occurred in it, and didn’t believe it had any connection with them.

כי אם ודאי ״ התנשא״ יוסף לפני עשרה. חלום האלומים כנראה מדבר על אחד עשר אחים. חלום הכוכבים על שמש, ירח ובפירוש על אחד עשר כוכבים, ובנקל להבין שבראשון דובר על האחים ו בשני על האב אשתו ואחיו. החלומות נתקיימו בזמן שירדו מצרימה, חלום ה שמש — ירידת יעקב והמשפחה, ואחיו יחד עם בנימין — חלום האלומים

If Yosef is really haughty before ten (I think this might be a question?). The dream of the sheaves probably speaks about the eleven brothers. The dream of the stars speaks about the sun, moon and eleven stars, so it’s easy to see that the first is talking about the brothers and the second about the father, his wife, and the brothers. The dreams were fulfilled at the time that they went down to Mitzrayim: the dream of the sun, when Yaakov went down with his family, and the dream of the sheaves when his brothers went down with Binyamin.

. אבל החלום המתאים לירידת עשרה אחים לא סופר, כי לא הבינו שבירידה ראשונה לא ירד בנימין אתם ולכן דובר כאן על עשרה.

However, the dream that corresponds to the descent of the ten brothers isn’t related, because they didn’t understand that at the first descent, Binyamin didn’t go down with them, and therefore that dream speaks only of ten.

תוכן החלום היה איפא, מה שהוא אשר סביבם. לא ייתכן שהמכוון לחקלאות, כי הם לא היו חקלאיים, ולא בכוכבים כי הם לא היו אסטרונומים. כי אם בעניני בית או עבודתם. ואחרי שלא ראה בו את האחים כמשתחוים לו ראו את החלום הזה כבטוי של גאוה, אבל בלי קשר ישיר אליהם, הם אמנם ״ הוסיפו לשנא אותו״ אבל אינם עונים לו כלום אחרי הספור.

The content [location] of the dream was where (I think this is a question)? What is in their surroundings. The meaning could not have been about agriculture, because they were not farmers, and it could not have been in the stars because they were not astronomers. Rather, it was about something close to home or to their work. And afterwards, the brothers didn’t see in it as bowing down to him, they saw the dream as an expression of pride, however, without any direct connection with themselves. They indeed “added to their hatred of him” but they didn’t respond in any way after he related the story.

ו) האחים שמעו כבר־ את החלום הראשון ורגזו עליו. כעת לא יכלו עוד לדברו לשלום. אבל ליוסף היה חלום אשר הרעיד אותו, והוא אינו יודע את פתרונו. בקש למצוא את פתרונו מאת אחיו. ״שמעו־נא״ הוא מבקש ואם בראשונה פתרתם לי חלום של התנשאות׳ הרי ״ חלום הזה אשר חלמתי״ דובר בו על מצבים בלתי רגילים אצלנו. על חקלאות, על קציר׳ והרי לנו אין שדות ולא עסקנו בקציר אף פעם.

The brothers had already heard the first dream and were mad at him. Now they couldn’t even speak peacefully with him anymore. However, Yosef had had a dream which shook him, and he didn’t know what its solution was. He asked his brothers to find its interpretation. “Hear now,” he asks them, “you interpreted my first dream as haughtiness,” and behold, “this dream which I have dreamed,” speaks within it of unusual situations among us, about agriculture, about reaping, and behold, we don’t even have fields and we have never occupied ourselves with reaping.

Comments

Post a Comment

I love your comments!